The Taranto-Capouya-Crespin Family History:

A Microcosm of Sephardic History

By Leon B. Taranto1

Part III. More on the Taranto, Capouya and Crespin Families

Taranto coat of arms:

Sea warrior on fish

A Jewish community lived on Rhodes in ancient Greek and Roman times, when the Colossus towered over the harbor. It survived centuries of Byzantine oppression and remained intact even until the late 1400s, when Rhodes was ruled by the knights of the Order of St. John, a Crusader force known also as the Hospitaliers. In the knights’ last days, around 1498-1502, the Jews of Rhodes were forced to convert to Catholicism or suffer exile, even though they had assisted the knights in defending the city against a powerful Turkish armada in 1480.2 Some submitted to forced conversion, remained in Rhodes, and practiced Judaism secretly. Others, refusing to betray their ancient faith, submitted to slavery or were banished.

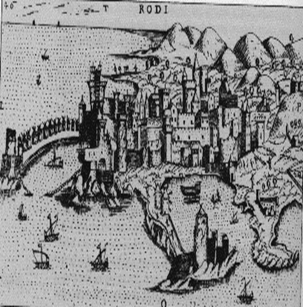

Turkish siege of Rhodes, 1480

In 1522 the Turkish navy again laid siege to Rhodes, this time successfully. Some historians suggest that the Ottoman capture of Rhodes succeeded partly because

of support the Turks received from conversos [forced converts] and other remnants of the Jewish community.3 The Ottoman conquest revived the Rhodes Jewish community as the sultan imported Jews from Salonika and other cities of the empire.4 Sultan Süleyman [Suleiman] the Magnificent and his successors encouraged Sephardim to settle in Rhodes, Izmir and other important towns of the Empire. Soon, the population inside Rhodes’ medieval city walls was composed entirely of Jews and Turks, as the Greeks were required to live outside.5

Like other Ottoman Jewish communities, the community on Rhodes likely grew quickly during the remainder of the 16th century, as the Ottoman Empire absorbed tens of thousands of Jewish refugees banished from Spain, Sicily, and southern Italy. As the numerous Sephardim arriving from Spain and Italy brought their advanced literary, scientific and technical skills, their Judeo-Spanish language and culture soon overwhelmed many of the empire’s Romaniote Jewish communities. In Salonika, lstanbul, Smyrna (Izmir), Edirne (Adrianople), Rhodes and many other cities, Ladino became the principal language of the Jews.6

In the wake of the Holocaust, few traces can be found on Rhodes of its long Sephardic history. In the one remaining synagogue, Kahal Shalom, a plaque dedicated by Yehdid Charhon, our Capouya cousin in France, memorializes the Capouya and other Jewish families of Rhodes who perished at the hands of the Germans.7 Another important sign of the historical Jewish presence on Rhodes are gravestones that survived the war. The one cemetery still intact houses graves of Bension Taranto's parents (Ephraim and Perla) and sister (Bulissa Sarah Habib), and a dozen Capouya, including Leah’s parents Raphael and Mazaltov (Fortuné).

From Southern Italy to the Sultan’s Lands

“Los Tarantos” movie poster

(from Nitza Maor)

The Taranto family name has been associated with the port of Taranto, in Apulia, southern Italy, along the Gulf of Taranto.8 Some recognize Taranto also as a Spanish name,9 particularly among the Gypsies (Roma) of Andalusia in southern Spain. The Taranto surname has also been associated with the city of Tarragona, on the Mediterranean coast of Spain, just south of Barcelona. A Sephardic community thrived in medieval Tarragona, until many Jews fleeing persecution left in 1290, for Rhodes; perhaps our Tarantos were among them?

In Granada, there is Gypsy cabaret in the Albassin district, and apparently a Flamenco dancing troupe, called Los Tarantos. Taranto is a part of the Flamenco tree, and Taranto (Taranta) is also a Flamenco dance.10 Los Tarantos is the title of a highly acclaimed award-winning movie about Gypsies in Spain, an Iberian “West Side Story.” Since Gypsies arrived in Spain around the time Sephardim were expelled, and while the Inquisition terrorized conversos and secret Jews remaining in Spain, we can imagine these targets of the Inquisition joining itinerant Gypsies to minimize their detection. Gypsies were allowed to live in Spain only as Catholics and soon were required to abandon their roaming life-style.11 Pere Bonnin’s book Sangre Judía, says the Taranto surname was found among Jews in Spain before the 1492 Expulsion.12

Beach on Spanish isle of Ibiza

Recent genetic evidence suggests a common origin for our Tarantos with the crypto-Jews who live on the Spanish isle of Ibiza today, in the western Mediterranean, just south of Majorca and Minorca, and a bit east of Barcelona and Tarragona. Most Jews of the Balearic Islands (Marjorca, Ibiza, etc.) were forcibly converted to Catholicism during the massacres that engulfed the Sephardic communities across Spain in 1391. Many of the forcibly converted of Ibiza and the other islands continued to practice Judaism in secrecy, for centuries, evolving into a crypto-Jewish group called the Chuetas that continued into the 20th century and narrowly escaped the Gestapo’s arrival at the welcome of Spanish fascists during the Second World War.

Antique map: port of Taranto, Italy, Hebrew University Collection

Antique map (ca 1600s?):

Taranto and Apulia region, Italy

Since the 1980s, Gloria Mound of Casa Shalom: The Institute of Marrano-Anusim Studies www.casa-shalom.com/ has extensively studied, written and lectured about the crypto-Jews of Ibiza. See Mound, “Survivors of the Spanish Exile: The Underground Jews of Ibiza,” Jerusalem Letter of Lasting Interest (10 Feb. 1988) www.jcpa.org/jl/hit12.htm. While Mound’s work has long interested me, only recently did I discover the fascinating genetic connection of our Tarantos to the crypto-Jews of Ibiza.

Ray Banks, a genetic genealogist who heads the Family Tree DNA project for the G2 Haplogroup, has advised that based on my Y-DNA analyses, I belong to the G2a3b1 cluster. The highest incidence of the G2a3b1 cluster is, by far, on the isle of Ibiza, where 16% of males tested have the same G2a3b1 finding. This finding is specific to Ibiza’s crypto-Jewish community. Banks reports that fully 88% of the G Haplogroup DNA samples from Ibiza are exact matches to the Sephardic DNA samples in a study by Israeli researchers Skorecki and Behar.13 As Banks points out, the crypto-Jewish community of Ibiza derives from Sephardim who lived there in the medieval era, before the Inquisition, and possibly back to the time of the Phoenicians.14

Taranto coat of arms:

gold crescent

In medieval times, prosperous Jewish communities existed in Sicily and southern Italy. The communities in Palermo, Capua, Taranto, Ostia, Brindisi and Otranto were already centuries old. Many had existed since Roman times, even predating Christianity.15 The scholarly traditions of the rabbis and Jewish communities of the port cities of Taranto and Bari in southern Italy were so well known by the 1100s that Rabbeinu Tam, a grandson of the outstanding 11th century rabbi Rashi of Troyes (France) wrote: “From out of Bari the Torah will go forth, and the word of G-d from Taranto.”16 In the 15th century, these communities produced famed translators of the Greco-Arabic classics, like Judah ben Solomon ibn Machta of Taranto and Samuel ben Jacob of Capua.17 But by century end, Jews faced annihilation in southern Italy, Spain and Portugal--places where they had enjoyed the greatest prosperity.

“Taranto’s” theater poster

On July 31, 1492, the day before Columbus sailed for the New World, the last Sephardim were forced to leave the Spanish kingdoms of Aragon and Castille. Since Ferdinand and Isabella also ruled Sicily, Sicilian Jews were also forced to abandon a homeland they had known over 1500 years.18 By some accounts, the deadline was extended three days to permit the Jews to observe the 9th of Av. Before century end, Sephardim also faced expulsion from the Kingdom of Navarre and a forced mass conversion in Portugal. Many Sephardim obtained refuge in southern Italy, in the Kingdom of Naples. Sicilian Jews also likely settled in Naples, Capua, Taranto and other towns of southern Italy.

By the early 1500s, the Spanish monarchs extended their control to southern Italy. They expelled all Jews, Sephardi and Italian alike, and instituted the Inquisition to root out the secret practice of Judaism among those who remained under the guise of Catholicism. Most Jews moved east to the Ottoman Empire, or to the Italian cities to the north – Padua, Ferrara, Livorno, Venice, Florence, Siena, Mantua, and Modena. The Inquisition operated in much of central and northern Italy, with the pope ordering the burning of secret Jews at the stake in Ancona. Subjected to oppressive restrictions, public humiliation, and persecution, many Jews left Italy and sought a haven in the Turkish dominions.

As Sephardi and Italian Jews settled in the Ottoman Empire, they sometimes adopted names of their native cities as surnames. By the mid-1500s, “Taranto” and other Jewish families with Italian and Iberian geographical surnames could be found in Istanbul (Constantinople), the sultan’s fast-growing capital:

The great port of Salonica, known as ‘the new Jerusalem,’ where Jews soon became a majority, was the bastion of Ottoman Judaism. However, there were 8,070 Jewish households in Constantinople by 1535, five times the figure in 1477. The names of the city's synagogues - Lisbon, Cordova, Messina, Ohrida - and families - Sevilia, Toledano, Leon, Taranto - reveal the diversity of their origins.19

Province of Taranto coat

of arms: scorpion

Though some Tarantos remain in Istanbul today,20 the Taranto surname became especially prominent among the Sephardim of Smyrna (Izmir), ancestral home for Bension’s family. There was no notable presence of Sephardim in Smyrna until the early 1600s,21 when the sultan developed it into a major seaport. To foster Smyrna’s growth, the Sultan induced many Jews from Salonika, Istanbul, Safed [Safat] and other cities to relocate there. Tarantos may have been part of this migration.

While there is some uncertainty as to the Tarantos’ origin, the Capouya family likely has its roots in southern Italy.22 Before changing to “Capouya,” the family name had been “MeCapua” or “Mi Capua,” meaning from Capua.23 When Ferdinand and Isabella expelled the Jews from the Kingdoms of Aragon and Castille (Spain) and from Sicily in 1492, many settled in Naples, and some must have migrated to nearby Capua. Jews had lived in Capua – where Spartacus’ slave revolt began – since at least Roman times. Most were abruptly expelled in 1510 and the remainder in 1540. “The Capouya ancestors must have left at this time and wandered until sometime between the 16th and 18th centuries when they went to Rhodes. It is possible that they lived for some time in Rome because there are references to Capuas on a World War I memorial tablet in a Jewish synagogue in Rome.”24 Perhaps some even went to London, where a Capua family was affiliated with the Sephardic Bevis Marks Congregation in the 1800s. A Capua family lived also in Tunis, where the Jewish community had strong familial and commercial ties to the Sephardim of Livorno [Leghorn] in Tuscany, Italy. “During the 18th century, due to the predominant influence of the French language, the name [for the family on Rhodes] was changed to Capouya."25

Capouyas and other Jews in southern Italy might have emigrated to Rhodes shortly after the isle fell to the Turks in 1522, or even earlier. Historian Howard Sachar mentions that in the early 1500s, the Kingdom of Naples also ruled the Dodecanese islands and suggests that Sephardim then settled there.26 Rhodes, as the principal island in the Dodecanese chain, would have likely received Sephardi emigrés.

Map: Sephardic migrations to Ottoman Empire from Haim Beinart’s Atlas

In reconstructing the Capouya family from the Spanish domains (southern Italy, etc.) to Turkey and Rhodes, it is important to recall that Jewish resettlement in Rhodes occurred well before the Ottoman Turkish conquest of 1522. The famed medieval Jewish traveler, Benjamin of Tudela, recorded in the journey of his travels during 1165-73 that 500 Jews then lived in Rhodes. Angel, Rottiers and other historians have written that in 1280, Jews fleeing persecution in Spain left Tarragona to make a new home in Rhodes. After the 1309 conquest of Rhodes by the crusading knights of the Order of St. John, life for Rhodian Jews vacillated from tranquil27 to tenuous, to intolerable. After the Turkish invasion of 1480 was repulsed, D'Aubusson, the Grand Master of the island, ordered the destruction of Jewish houses to supply material for reconstructing a wall damaged in the Turkish attack. The Jews were then ordered to convert to Christianity. Some submitted to baptism, while others chose slavery or death. On January 9, 1502, the grand master issued an expulsion decree, resulting in the exile of some Jews to Nice, in Provençal France.28 D’Aubusson’s death prevented the decree’s full enforcement, and conditions improved for the remaining Jews.

Rhodes: (a) Medieval city walls and (b) Street of the Knights of Rhodes

When the Turks conquered Rhodes in 1522, the Jewish community began anew. Some converts likely returned to their ancient faith. Sultan Süleyman, to develop the isle, brought a dozen families from Salonika and granted special privileges: 20-year exemption from taxes, free housing, and sulfur mining rights. Sephardi emigres from Spain, Italy and the Ottoman Empire likely settled in Rhodes at that time. Capouyas might have arrived with them, if not already ashore welcoming them.

European woodcut map of medieval Rhodes

Within the Ottoman Empire, the Capouya name was not unique to Rhodes. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, at least 21 “MeCapua” brides and 25 grooms were married in Izmir.29 From 1934 to 1969, 18 “Kapuya” were buried in Izmir. Since Sephardi settlement in Izmir did not really begin until the start of the 17th century when the sultan transplanted Jews there from other parts of the empire, some Capouya might have come to Izmir from Rhodes. In 1691, Rabbi Abraham MeCapoua headed the Jewish community in Kusadasi, an ancient port south of Izmir.30

A Matriarch Is Born

Rabbi Isaac Aboab

of Amsterdam, first

rabbi in the New World,

1600s

One matriarchal ancestor for Bension is believed to be Rebecca Beresit (Berecit), probably his great-grandmother - his mother Perla Beresit Taranto’s paternal grandmother. A surviving fragment of our family history is this fascinating story of Rebecca from a cousin who shares our Capouya and Beresit ancestry.31

Around 200 years ago in Izmir there lived a woman with many daughters (6 or 7), but no sons. Becoming pregnant again, she gave birth to yet another daughter. About the same time, one of her older daughters bore a child – but the infant was not born alive. The aging matriarch had her newborn infant taken and wrapped to be presented to her older daughter, to raise the child as her own. This newborn, Rebecca Beresit (presumably her married name), was raised by her adoptive mother, who was of course her older sister. When the adoptive mother died, Rebecca wanted to perform the religious rites to mourn the loss of her mother. Ignorant of the circumstances of her birth, Rebecca was told that she could not mourn her mother's loss as this was really her sister. In time, Rebecca gave birth to a son, Raffael Beresit, who married Esther Aboaf.

The surname Aboaf (variant spellings: Abouaf, Aboav, Abuaf, Aboab) is richly associated with Sephardic history in pre-Expulsion Spain,32 and after the 1400s in northern Italy, the Netherlands, and the Ottoman Empire.33 Following the 1492 expulsion from Spain and shortly afterwards from Portugal and Navarre, they eventually spread out to Italy (Venice),34 Holland (Amsterdam),35 Germany (Hamburg),36 the Adriatic coast of the Balkans (Corfu), and Ottoman Turkey (e.g. Izmir, Milas, Rhodes). 37 The New World’s first rabbi was Isaac (Yitzhak) Aboab de Fonseca, who arrived from Amsterdam in the Dutch colony of Recife, Brasil, in 1644. After the Portuguese recaptured the colony from the Dutch, Rabbi Aboab led 600 Jewish colonists (of the 1,450 to 5,000 who had flourished in this largest Jewish settlement in the Americas) back to Amsterdam. Some headed north to the Caribbean and Surinam, including a small group that was blown off course and in 1654 arrived in New Amsterdam. They became the first permanent Jewish settlers in New York and the United States. www.jodensavanne.sr.org/article5.html38

Raffaele Beresit and Esther Aboaf had at least two children: (1) Perla, who married Behor Ephraim Taranto and gave birth to Bension; and (2) Mazaltov (wed to Bension Billi),39 whose descendants intermarried with our Capouya and Taranto families.40 Some Beresit family members remain in Izmir even today. There are dozens of entries for the Beresit family on the lists of brides and grooms of Izmir,41 and in the register of Jews buried in Izmir. The tale of Rebecca Beresit might provide us a key for learning more about our family origins as we make contact with Beresit family members remaining in Izmir.

Beresit likely derives from Bereshit, Hebrew for Genesis, the first book of the Bible. Variants include Beresi, Beressi, and Bedersi. The family likely originated in Beziers, a town in southern France that was known to medieval Jews as “the little Jerusalem.” As Bederesi was a Jewish-owned estate near Beziers, mentioned in a document from the year 990, Jews from that area were known as Beresi or Bederesi. The Jews were expelled from Beziers in 1307, allowed to return in 1367, and exiled again in the 1390s when France expelled all its Jews. Some Beresi (Beressi) arrived in Salonika in the Ottoman era, and lived there until the Germans destroyed the Jewish community during the Second World War.42

Travels from the Juderias of Navarre and Castile

At the beginning of 1498, the Sephardim of the Kingdom of Navarre were the last openly practicing Jews in Spain or Portugal.43 Landlocked Navarre, located in the Basque country of present-day Spain, was sandwiched between the powerful kingdoms of France and Castille. One Sephardi family in Navarre was the Crespin44 family of the town of Tudela. Crespins had lived in Tudela since the late 1100s (1160-1180),45 and perhaps much earlier. Some Jewish communities of medieval Navarre, like Pamplona, were of relatively recent origin. The Judería of Tudela, however, was already old by the 1100s. Jews lived in Tudela even before the Spanish Christians captured the region from the Moors at the outset of the Reconquista.46 By the 12th century, Crespins were making important contributions to philosophy, poetry, and religion.47

Beresit-Aboaf family chart, 1800s

Like many Jews of 12th century Navarre, Crespins may have originated elsewhere. Many were refugees from the attacking Moorish tribes sweeping into Islamic Spain during the first half of the century. Like the family of Maimonides, thousands of Jews from Cordova and other communities fled for safety and religious freedom. Many found a haven in the Christian kingdoms of northern Spain. Perhaps Crespins were among them. Another possibility is that Crespins came to Navarre from France. Crespin is a French name, and northern Spain was a logical refuge for French Jews fleeing Crusader armies and anti-Semitic outbreaks. Variants of the Crespin name appeared also among Jewish communities in the medieval Spanish Kingdom of Aragon, including Abincresp in Calatayd in 1229, and Abincrespin in Valencia in 1292.48 Geographical associations for the Crespin surname provide another clue for the family origin.49

The end came for Navarrese Jewry in 1498 as King Johan and Queen Catalina issued an edict of expulsion.50 Navarre’s rulers had succumbed to the pressures from their powerful Spanish neighbors, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, who only six years earlier had expelled all Jews from the Spanish kingdoms of Aragon and Castille.

Toledo

Before the 1492 expulsion, a Jewish family Crespin lived in Castille, in the city of Toledo. In the 1480s, the Crespins of Toledo commissioned the preparation of a Bible that survives today.51 Also, a manuscript of ordinances promulgated by Jewish delegates of the Kingdom of Castile summoned in 1432 by its Chief Rabbi Don Abraham Benveniste to an assembly in Valladolid is signed by Isaac Ha-Kohen b. Joseph Ha-Kohen b. Crispini as witness.52

In the 1200s, Crespins lived among the small Jewish community in England, until King Edward I expelled all Jews in 1290. At least one prominent Crespin family of London was among the thousands of Jews deported:

The Crespins were one of the leading Jewish families in London in the 1200s. Like most English Jews their wealth depended on money-lending and financial dealings. In 1244 Moses Crespin inherited from his father Jacob a house in Milk Street, north of Cheapside. It lay in a row of stone houses, several of which were occupied by Jewish families. Moses or his father built a mikveh, the ritual bath essential to Jewish religion, in the cellar of the house. In 1290 Moses and his family were among the 4,000 to 16,000 Jews deported from England on the orders of King Edward I. His house, valued at £3 19 shillings, was confiscated and granted to Martin Ferraunt, a servant of Queen Eleanor. 53

The Crespins might have begun their journey to the Levant in the wake of the expulsions of 1492 and 1498. Our ancestor Rabbi Mordehay Crespin (Krespin), son-in-law to Rhodes Grand Rabbi Moshe Israel (1670-1740) and son of Rabbi Itzhak (Yitzhak) Crespin (Crispin) of Salonika, was born around 1725-30 in Salonika, and died circa 1790 on Rhodes, where he was a rabbi and ultimately chief of the Beit-Din, or Rabbinical Court.54 Dov Cohen suggests that Mordehay’s father Rabbi Itzhak Crespin might be the same Rabbi Itzhak Crespin of Salonika who was the son of Rabbi Menahem Crespin, taking our Crespin family to the mid-1600s.

In the 1600s, there was also a Crespin family with branches in the quickly growing Sephardi communities in the burgeoning ports of Livorno (Italy) and Smyrna (Izmir). In 1592, Ferdinand dei Medici (Ferdinand I), Grand Duke of Tuscany, invited the Sephardim to settle in Livorno and Pisa and freely practice their religion. As the Duke hoped, the Sephardim transformed Livorno into a vital commercial port, enriching Tuscany. Dov Cohen recently found archival records in Livorno showing that in 1644 a Yehuda Crespin of Livorno and others founded the Dotar Company, operating in Livorno and Smyrna. The company provided support to orphan girls for their weddings. A registry of company members shows the transfer of its membership from Livorno to Smyrna. Dov Cohen explains that Yehuda Crespin transferred his membership to his son Joseph, which was later transferred to Joseph’s son Moshe. Moshe died unmarried, leaving his membership to his brother Daniel Crespin, who died in Smyrna with no male heirs. Curiously, our 19th century ancestor Haham Yehuda Crespin was born in Smyrna around 1812, moved to Livorno where he was a banker, and then returned to Smyrna before 1871, when he appears in the Tuscan register. Whether or how our Yehuda Crespin is related to the mid-1600s Yehuda Crespin, also of Livorno and Smyrna, remains a mystery.

By the late 1700s, our Crespin family settled in Smyrna, where Leah Capouya Taranto’s mother Mazaltov (Fortunée) Crespin was born between 1846 and the early 1850s. On January 26, 1866, Mazaltov wed Raphael Capouya in Rhodes. Coincidentally, Mazaltov’s father Yehuda Crespin’s sister Joya (Coya/Joia) Crespin (b. ca 1820 or 1830 Smyrna, d. 30 Aug. 1890 Smyrna) wed Behor Haim Moshe (Moise) Taranto (b. 1817 Smyrna, d. 1909 or 1913 Smyrna), a second cousin to our ancestor Bension’s father Behor Efraim Taranto (b. ca 1825 Smyrna, d. 1876 Rhodes). As a result, the descendants of Behor Haim Moshe Taranto and Joya Crespin are not only our double cousins, but also more closely related to us through the Crespin family than on the Taranto side.

For our Crespins, the journey from Spain to Rhodes spanned centuries. Their 12th century neighbor, Benjamin of Tudela, traveled from his native Spain throughout the Jewish world in only eight years (1165-1173), chronicling his visits to Capua, Otranto, Constantinople, Rhodes, Antioch, Cairo, Alexandria, Damascus, Baghdad, and other communities.55 His journeys from Navarre to Turkey and Rhodes charted a path for the Crespins of later centuries.

By the 1600s to 1700s, Crespins flourished in the Ottoman Empire as rabbis, teachers, journalists, and authors of religious treatises, primarily in Salonika and Izmir, but also Yambol (Bulgaria), Rumelia (Rumania), and Rhodes. In the 1800s, several Crespin were important rabbis in Izmir. Shelomo Krispin was one of the young rabbis who led the Jewish community 1840-42, and drawn into a class cleavage quarrel that in 1847 split the community along economic lines.56 Rabbi Yom Tov Crespin authored the book Bigdei Yom Tov, 1887.57 Samuel Crespin of 19th century Izmir was a rabbinical author who wrote Meshek Beti [Steward of My House], Gen. xv. 2, novellae to the Talmud, 2 vols., Salonika, 1833; his father was Izmir’s chief rabbi, Joshua Abraham Crespin.58 Elias Crespin was a Rumanian rabbi, teacher, and journalist, born about 1850 at Eskee Sara, eastern Rumelia; he fled to Rumania after the 1878 Turco-Russian War, and founded a Judeo-Spanish journal in Latin characters, El Luzero de la Paciencia, published 1886-87.59 This identifies only a few prominent Crespin rabbis; there were others.60

Leon Bension Taranto & Leah Capouya family chart

An important community leader was Nissim Crespin, who in the 1860s played a central role establishing the Alliance Israélite Universelle schools in Izmir.61 Also called Nissim Habib Crespin (1829-1891), he was the brother of our ancestor Haham Yehuda Crespin (b. ca 1812, d. 1885) and Joya Crespin Taranto (b. 1820 or 1830, d. 1890). Rachel Crispin was an AIU teacher in Izmir, and the second wife to Gabriel Arie, the AIU leader for Izmir.62 Some Crespin remain in Izmir today.63 Our Crespin branch has spread worldwide, to France, Belgium, Switzerland, Israel, South Africa, Brazil, Argentina, Venezuela, Mexico, Canada, and the United States.

Epilogue

Leah and Bension’s descendants live freely today. Our 2000-year odyssey has taken us from ancient Israel, to the flourishing Jewish quarters of medieval Spain and Italy, the Ottoman Empire (Rhodes, Izmir, Salonika, and Jerusalem), and finally America. Our Sephardi families - Taranto, Capouya, Crespin, Beresit (Bedressi), Bonomo, Algranate, Capelluto, Abouaf, Israel, Ben-Habib (Habib) - span six continents. Though dispersed, our proud heritage unites us.

This is the third part of a three-part series on Sephardic Horizons. Part one. Part two.

Notes:

1. Leon Taranto is a native of Atlanta and a Washington DC attorney who is active in Sephardic genealogy. He is an organizer and planning committee member for Vijitas de Alhad of the Greater Washington DC area. He has authored articles for Sephardic and Jewish genealogical journals on the Jews of the Ottoman Empire and Mediterranean Basin, and presented at international conferences on Jewish genealogy, to genealogical societies, and at synagogue-hosted events. For the extensive bibliography relating to this article, please see Part I in the earlier issue of Sephardic Horizons, 1:4 (Summer-Fall 2011).

2. Angel, The Jews of Rhodes, The History of a Sephardic Community, Sepher-Hermon Press, New York, 1978, pp. 17-18; Mattis Kantor, The Jewish Timeline Encyclopedia: A Year-By-Year History From Creation To The Present, Jason Aronson, Inc., Northvale, NJ, 1992, pp. 183-84 (expulsion of Sephardi refugees and other Rhodian Jews to Nice in 1498); Isaac Jack Levy, Jewish Rhodes: A Lost Culture, (Berkeley: Judah L. Magnes Museum, 1989), p. 22 (The grand master’s expulsion decree of 1502 ordered all Jews removed to Nice within 90 days under penalty of torture, death or slavery unless they embraced Catholicism. Jewish children were forcibly converted and kept on Rhodes. The grand master’s death prevented the full execution of the decree and many Jews remained on Rhodes.).

3. Angel, The Jews of Rhodes, supra, p. 19 (one claimed witness to the siege reported that between 2,000 and 3,000 Jews assisted the attacking Turks by filling the moat with sand bags by the Italian portion of the city walls).

4. Angel, The Jews of Rhodes, supra, p. 21. Ruth Porter and Sarah Hare-Hoshen, Odyssey of the Exiles - The Sephardi Jews 1492-1992, (Tel Aviv: Bet Hatefutsot, 1992), p. 98 (sultan relocates 150 Jewish families from Salonika to Rhodes).

5. For a comprehensive history of the Rhodeslis, see Angel, The Jews of Rhodes, supra.

6. Levy, Jewish Rhodes: A Lost Culture, supra, pp. 26-27; Angel, The Jews of Rhodes, supra, pp. 22-23.

7. Yedid’s mother, Sarota Capouya, was Leah Capouya’s sister. Sarota married Asher Charhon in Rhodes. After Asher’s death, she moved to Paris with her children, in birth order: Yedid, Jacques, Albert, Flore (died in concentration camp), Leon (lived in Paris as did his brothers, now deceased), and Olga Charhon Franco (lived in Brussels until her death in 2003). “Yedid Charhon hid out in Southern France with his Mother during World War II, as did Jacques. Albert escaped across the Channel to England. Leon walked across the Pyrenees to Spain. Olga was living in the Belgian Congo during the Nazi occupation of Paris. Her husband was murdered in the Congo. Yedid Charhon donated an immense amount of money” to restore the Rhodes synagogue and cemetery. Capouya family histories provided by Morris Nace Capouya and Melvyn Halfon, 1997.

8. Pinto, What's Behind A Name, The Sephardic Onomasticon (Istanbul: Gozelem, 2004); Bob Bedford, “Brief Overview of the Taranto Family Name,” supra.

9. A hotel clerk in Seville recognized our Taranto as a Spanish name and told me that I must know Spanish. Also, my friend Ralph Tarica, an Atlanta native and retired professor of French, suggests that Taranto is a Spanish surname and not necessarily associated with Taranto, Italy.

10. For links to Gypsy associations with the name Taranto, search www.google.com using 'Gypsy' (or 'Gypsies' or 'Flamenco') and 'Taranto' as key words. See Leon Taranto, "Izmir and Rhodes: Taranto Family Origins, Archives, and Links to other Sephardim," ETSI - Revue de Genéalogie et d'Histoire Sépharades (Sephardi Genealogical and Historical Review), vol. 15, pp. 3-9, Dec. 2001.

11. In Noah Gordon’s novel, The Last Jew, Yonah Toledano, a teen left behind in Toledo after the 31 July 1492 deadline for Jews to leave Spain, finds temporary refuge with the Roma who settled in Granada.

12. Pere Bonnin, Sangre Judia, Flor del Viento Ediciones, Spain 1998 (3d ed.), listing Jewish family associated with pre-Expulsion Spain, and Anusim/Conversos and the Spanish Inquisition, including: Aboab, Bedarsi (Beresit), Bonomo, Crespin, Israel, and Taranto. Bonnin’s 4th edition does not list Taranto but, according to Sephardic genealogist and friend Schelly Dardashti, Bonnin lists Algranati (1306 Pampalona), Crespin (1318 Tudela), Crespi (1298 Taragona), Cresp (1369 Valls, (Santa Columa de Queralt), Bonomo Figueres, Girona), Bono (1351, Esplunga, Tarragona), Bonhom (992 Barcelona), Bonhome (1372 Figueres), BedarsiBedersi (1240 Perpignan, French Catalunya), and Algranate variants in Toledo (Granate (1487; Granado 1417; and Granada 1551).

13. In an April 5, 2010 email, Ray Banks writes:

Published research in late 2008 and in early 2009, relative to Iberian G persons and more particularly to Ibiza Island further suggest a Jewish connection for two of the three main G2a3b1 groups (DYS388=13 and DYS568= 9) The 2008 study suggested that Ibizan haplogroup G samples, in contrast to the R and E haplogroups in Iberia, have heavy admixture of sample features seen among Sephardic Jews. The Jewish samples came from Israeli researchers Carl Skorecki and Doron Behar's Sephardic Jewish samples. (Susan M. Adams et. al, "The Genetic Legacy of Religious Diversity and Intolerance: Paternal Lineages of Christians, Jews and Muslims in the Iberian Peninsula," Amer. J. Human Genetics, 2008, vol. 83, pp. 725-36).

Some samples were provided in this study from the island of Ibiza, the smallest of the Balearics. Then in 2009, was published V. Rodriguez, "Genetic Sub-structure in Western Mediterranean Populations Revealed by 12-Chromosome STR Loci," Internat’l J. Legal Med., 2009, vol. 123, pp 137-41. While neither of these studies checked the samples for the presence of P303 which defines G2a3b1, it is clear from the marker values that these are P303+ (G2ab3b1) samples. There is great similarity to the samples, and the Adams study found that about half had 12 for DYS388 and half had 13. Thus there is great likelihood these samples properly belong to the DYS568=9 and DYS388=13 subgroups of G2a3b1.

Combining the two studies which have over 150 Ibiza samples, there are about 16% G2a3b1 persons in Ibiza -- the highest percentage of G2a3b1 by far of any location in the world. Comparing Ibiza's larger number of samples in the Rodriguez study to the Sephardic samples found only in the Adams study, one finds that 88% of the G samples of Ibiza are exact matches to Sephardic samples, but only 22% of the R1b Ibiza samples are exact matches to Sephardic samples. There are only a relatively few Ibiza samples that aren't R1b or G and the percentages of matches may be too coincidental at such low numbers to consider them for comparisons.

When one excludes the majority haplogroup R and E samples from the Ibiza data because of their apparent extremely high relationship to non-Jewish groupings, one is left with haplogroup G as the prime candidate for Jewish ancestry on the island. ...

14. Ray Banks writes: “[T]here had been a flourishing Jewish presence on the island from Phoenician times even during the Spanish Inquisition during which they were able to maintain their Jewish communities in secret at their remote location. This was facilitated by a long history of traditional secrecy with outsiders related to the smuggling for which the island was famed. It is not easy to quantify the percentages of descendants of original Jews there. Various sources give different information, but the quantity was certainly under 50% but still substantial. The population in the Middle Ages on the island was only a few thousand persons with four Christian churches in existence. Some Christian buildings had secret synagogues below them, and some of the Christian population observed Saturday as a work-free day. See www.jcpa.org/jl/hit12.htm by Gloria Mound for detailed information on the Jewish presence in Ibiza. ...

15. Martin Gilbert, Jewish Historical Atlas (Collier Books, New York, 1969, pp. 10, 14-15. Haim Beinart, Atlas of Medieval Jewish History, Carta, The Israel Map Publishing Co., Ltd., 1992, pp. 13-14. Marvin Lowenthal, A World Passed By - Great Cities in Jewish Diaspora History, Harper & Bros., New York, 1933, republished under same title, Joseph Simon, ed., Pangloss Press, 1990, pp. 244-51.

16. Andreé Brooks, “In Italian Dust, Signs of a Past Jewish Life,” New York Times, 15 May 2003 www.nytimes.com/2003/05/15/arts/design/15VENO.html?pagewanted=all&position

17. Howard Sachar, Farewell Espana - The World of the Sephardim Remembered, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1994, p. 218.

18. By some accounts, the deadline for the Expulsion was extended another three days to allow the departing Sephardim to observe the fast of Tisha Ba’av.

19. Philip Mansel, Constantinople - City of the World’s Desire: 1453-1924, St. Martin’s Press, New York, 1996, p. 123. In 1477, about 9% of Constantinople's population of 100,000 were Jewish. By 1689, the city's population reached 600,000, about 8% (i.e., 48,000) Jewish. Mansel, p. 437.

20. Dr. Izzet de Taranto, a physician from a “famous” Sephardi family, emigrated from Istanbul and died in the United States before 1971. That year, the last French-language daily newspaper in Istanbul lamented the loss of Dr. Taranto and other prominent members of old Istanbul families who left for foreign lands. Mansel, Constantinople - City of the World’s Desire: 1453-1924, pp. 427, 486 n.27.

21. A Jewish community existed in the vicinity of Izmir during Roman times, but massacres and persecutions during the Byzantine centuries entirely wiped out this ancient community. In the Ottoman era, “[t]he first mention of a Jewish community in Izmir comes in 1604-20, when a series of fires and attacks in Salonica caused many Jews to move across the Aegean.” Stanford J. Shaw, The Jews of the Ottoman Empire and the Turkish Republic, (New York: NYU Press, 1992), pp. 129-30. But individual Jews collected tax revenues at the port starting around 1600. Goffman, Izmir and the Levantine World, 1550-1650 (Seattle: Univ. of Washington Press, 1990.

22. A more remote possibility was suggested to me when I visited Spain four years ago. Hearing the name “Capouya,” a merchant in Toledo associated it with the similarly sounding Spanish word “capullo.” It refers to one who is budding, like a flower. When said of a young woman, it is a compliment. But it has a derogatory connotation when used for a man.

23. Capouya family histories, supra.

24. Capouya family histories, supra.

25. Capouya family histories, supra.

26. Sachar, Farewell Espana - The World of the Sephardim Remembered, supra.

27. A travel account by Rabbi Meshullam Ben R. Menachem of Volterra chronicles his arrival in Rhodes on May 4, 1481 (5241), and its Jewish community in the pre-Ottoman era. He comments that the Turks had laid waste to the city, especially to the Jewish quarter since the principal fighting was there, and recounts a “miracle” at the synagogue that saved the life of the Gran Maestro from 10,000 attacking Turks who ascended the synagogue walls. The Rabbi adds that “there are many villages on the Island and the Jews live there in perfect tranquility.” Elkan Nathan Adler, Jewish Travelers, 1930, republished as Jewish Travelers in the Middle Ages - 19 Firsthand Accounts, Dover Publications, New York, 1987.

28. At the end of the 15th century, many Jews of Provence were likewise forced to convert. Michel de Nostradame, the famed Nostradamus, was among those born into recently Christianized families of Provençal Jews. His clandestine study of Kabbalah likely played a major role in shaping the renowned prophecies we still read today.

29. Cohen, Izmir - List of 7300 Names of Jewish Brides and Grooms Who Were Married in Izmir Between the Years 1883-1901 & 1918-1933, supra; Roland Taranto, “Les Noms de Famille Juifs de Smyrne,” ETSI Revue 5:16 (Mar. 2002), p. 6. ‘MeCapua,’ a transliteration from Hebrew or Solitreo characters, is almost certainly the same name as MeCapouya or Capouya.

30. Abraham Galante, Les Juifs d’Anatolie (part 2).

31. Sarina Capouya Rousso (1898-2002) repeated this story over the years to her granddaughter Sarah Tourial Grosswald. Sarina was a first cousin to Leah Capouya Taranto. Their fathers, Jacob and Raphael, were brothers.

32. For example, Menoras Hamaor, written by Rabbeinu Yitzchak Abohav of Spain over 600 years ago, is regarded as a great classic of Torah literature. Menoras Hamaor: The Weekday Festivals – Rosh Chodesh – Chanukah – Purim – An Annotated Excerpt, translated by Rabbi Yaakov Yosef Reinman, C.I.S. Publication Div., Lakewood, NJ, 1986. See also “Jewish History Sourcebook: The Expulsion from Spain, 1492 CE” www.fordham.edu/halsall/jewish/1492-jews-spain1.html (in Spain at time of 1492 expulsion).

33. Rabbi Angel writes of several Aboab family members, including Imanuel Aboab, who facilitated the return of Conversos to Judaism, and his Nosmologia, a Spanish text arguing for the authenticity of the Oral Torah; Shemuel Aboab, a 17th century Italian rabbi who, writing in Venice (perhaps late 1660s), criticized the Jewish communities that had given credence to the false Messiah, Sabbatei Sevi; and Yitzhak Aboab de Fonseca, a rabbi of 17th century Amsterdam. Marc D. Angel, Voices in Exile - A Study in Sephardic Intellectual History, Ktav Publishing House, Hoboken, NJ., and Sephardic House, New York, 1991, pp. 51, 62. 66, 76, 81.

34. Brian Pullan, in The Jews of Europe and the Inquisition of Venice, 1550-1670, writes of two men of the Aboab family. He comments that Samuel Aboab moved from Verona, Italy, to become the Rabbi of the Ponentine community of Venice in 1650. Rabbi Aboab “was especially eager for the absorption of the Marranos into the Jewish community” and urged that “‘there should be in each and every city of Israel a special brotherhood for this purpose.’” He also refers to Abram Aboaf, a Portuguese Jew living in Venice in 1635. Brian Pullan, The Jews of Europe and the Inquisition of Venice, 1550-1670, Barnes & Noble, and Blackwell Publishers, 1997, pp. 210, 227. Cecil Roth, in History of the Jews in Venice, Schocken Books, New York, 1975, discusses various Aboab families in Venice, who were from Lisbon and associated with Sephardi émigrés in Antwerp, Hamburg, Altona, and Verona.

35. Susan W. Morgenstein and Ruth E. Levine, The Jews in the Age of Rembrandt, Judaic Museum of the Jewish Community Center of Greater Washington, Rockville, 1981, p. 67 (photo of Rabbi Isaac (Yshack) Aboab de Fonseca, born in Portugal, arrived as a child in Amsterdam, sailed in 1641 to become haham to the new Dutch settlement at Pernambuco (Recife) in Brasil and first rabbi in the Americas, returned to Amsterdam in 1654 after the Portuguese recaptured Brazil and exiled the Jews, became senior assistant to the Sephardi community in Amsterdam in 1659, and inspired the construction of the great Portuguese Synagogue in 1675).

36. Roth, History of the Jews in Venice, supra.

37. There is a considerable literature for this family. See Pinto, What's Behind A Name, supra; The Jewish Encyclopedia, Funk & Wagnalls, vol. 1, pp. 72-75, 1901, vol. 1; Miriam Bodian, Hebrews of the Portuguese Nation: Conversos and Community in Early Modern Amsterdam, Indiana Univ. Press, Bloomington, 1997; Roth, History of the Jews in Venice, supra; Morgenstein and Levine, The Jews in the Age of Rembrandt, supra, p. 67.

38. See Morgenstein and Levine, The Jews in the Age of Rembrandt, supra, p. 67, and note 142.

39. The 1938 Italian census of the Rhodes Jewish community lists Mazaltov Berescit, who married Bension (Eli) Billis (or Billi) as the daughter of Raffael Berescit and Ester Aboaf. With the census data for her sister Mazaltov, we can identify Perla's parents as Raffael Berescit (Beresit) and Ester Aboaf.

40. Mazaltov and Bension Billi’s daughters Rosa (wed to Avram Franco), and Reina (who married Sidkiah Tourial), settled in Atlanta. Rosa’s grandson Morris Habib married Bertha Yohai of our Taranto family, and Reina’s sons Ralph and Eli Tourial chose as their wives two of our Capoya cousins, Regina Rousso and Pat Capouya. Cousin Sonja Bilé Vansteenkiste, granddaughter to the elder of Mazaltov’s two sons who settled in Belgium a cetuury ago, provides fascinating chronicles for her branch of our Beresit family in “La Révélation Extraordinarie de Mes Racines Juives Séfarades d”Izmir,” ETSI, vol. 11, no. 43, Paris, and in the Dutch and truncated English versions of her book Grootvader Leon Bilé, zijn & mijn geschiedeis (Granddad Leon Bilé, his story and my story), Blankenberge, Belgium, 2010.

41. R. Taranto, “Les Nomes de Famille Juifs de Smyrne,” supra; Cohen, Izmir - List of 7300 Names of Jewish Brides and Grooms Who Were Married in Izmir Between the Years 1883-1901 & 1918-1933, supra.

42. Pinto, What's Behind A Name, supra, pp. 132, 304, 432.

43. Benjamin R. Gampel, The Last Jews on Iberian Soil - Navarrese Jewry 1479-1498, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1989; Benjamin R. Gampel, “The Exiles of 1492 in the Kingdom of Navarre: A Biographical Perspective,” pp. 104-117 in Crisis and Creativity in the Sephardic World: 1391-1648, Benjamin R. Gampel, ed., Columbia Univ. Press, New York, 1997.

44. Crespin name variants likely include Crespel, Crespi, Crispi, Crispin, Krespin and such Latin derivatives as Crispus, Crispinus, and Krispil. See also R. Taranto, “Les Nomes de Famille Juifs de Smyrne,” supra, p. 8: “Crespin: Nom propre que l'on trouve dans le Talmud sous la forme Crispus ou Crispinus. Ce nom es tres fréquent en Roumanie et en Turquie. Krispi(e)l - Crispi(e)n - Cri(e)spi - Crespel.” Crispus seems curious as a Jewish surname as this was the name of the first-born son of Constantine, the first Christian to become Roman Emperor, dubbed Constantine the Great since he imposed Christianity as the state religion of Rome. Constantine killed his wife and son Crispus, and many other members of his family. James Carroll, The Sword of Constantine: The Church and the Jews - A History, Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston and New York, 2001, pp. 202-04.

45. Beatrice Leroy, The Jews of Navarre in the Late Middle Ages, The Magnes Press, Hebrew University: Jerusalem, Hispania Judaica Series vol. 4, pp. 12-14, 1985.

46. Leroy, The Jews of Navarre in the Late Middle Ages, supra, pp. 12-14.

47. Yitsjak Crespin (circa 1100-1200) was considered the grand prince as philosopher, moralistic poet, and religious poet. His book on ethics, Sefer Hamusar, ends with a religious poem. As noted by Al-Hazari (1170/1235), a historian and philosopher of Moorish Spain, “the poems of Crespin are all beautiful and ingenuous.” Ben Nahman email, citing Nissim Elnecave, Los Hijos de Ibero Franconia (Argentina).

48. Jean Régné, History of the Jews in Aragon: regesta and documents, 1213-1327, Hispania Judaica, v.1, Jerusalem: Magnes Press, Hebrew Univ., 1978 (index compiled by Mathilde Tagger at www.sephardicgen.com/databases/databases.html )

49. A friend in Israel, Mathilde Tagger, pointed to possible associations with towns in northern Italy (Crispian), central Spain (Crespos in Avila province) and the south of France (Crespian).

50. Gampel, The Last Jews on Iberian Soil - Navarrese Jewry 1479-1498, supra; Kantor, The Jewish Timeline Encyclopedia, supra, pp. 183-84.

51. The Jewish Bible commissioned in the 1480s by the Crespin family of Toledo was auctioned by Sotheby's several years ago.

52. Medieval Sourcebook: Synod of Castilian Jews, 1432, www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/1433synod-castile-jews.html

53. Robin R. Mundill, England’s Jewish Solution: Experiment and Expulsion, 1262-1290, Cambridge Univ. Press, 1998.

54. The book Oriental Jews in Erets Israel by Sir Moshe David Gaon, Yehudei haMizrah beErets Yisrael, Jerusalem, 1938 (translated from Hebrew by Mathilde Tagger), identifies him as Rabbi Mordekhay Crispin, born 1730 Salonika, son of Yitchak Crispin. He moved to Rhodes, where he was a rabbi. Dov Cohen places his birth around 1725, and death about 1790.

55. Benjamin visited Jewish communities in Italy, Greece, Turkey, Syria, Israel, Egypt, Yemen, Iraq, Iran, Uzbekistan, India, Ceylon, and perhaps China. Adler, Jewish Travelers in the Middle Ages, supra, p. 38; Beinart, Atlas of Medieval Jewish History, supra, pp. 44-45; Pinto, What's in a Name, supra, pp. 120-21.

56. Avner Levi, "Shavat Aniim: Social Cleavage, Class War and Leadership in the Sephardi Community - The Case of Izmir 1847," pp. 184-202 in Ottoman and Turkish Jewry - Community and Leadership, ed. Aron Rodrigue, Indiana University Turkish Studies, 1992.

57. Sharsheret Hadorot, vol. 5, no. 3, part II, Israel Genealogical Society: Jerusalem, Oct. 1991. An internet link displays an image of the book Bigdei Yom Tov, by Yom Tov Krispin, 1873 Smyrna.

58. “Samuel Crespin,” The Jewish Encyclopedia, supra, vol. 9, p. 354. An internet link shows an image of the book as Meshek Beti, by Samuel Krispin, Salonika, 1798.

59. “Elias Crespin,” The Jewish Encyclopedia, supra, vol. 9, p. 354.

60. See Shaul, “Summary of a Recent Lecture: Tracing the Family from Izmir (Smyrna) and Yugoslavia to Eretz Israel,” Studies in Sephardic Culture - The David N. Barocas Memorial Volume, ed., Marc D. Angel, Sepher-Hermon Press, New York, 1980, p. 34 (Crespin of Yambol, Bulgaria published Judeo-Spanish proverbs in his monthly magazine, La Alvorada, which he edited in Rumania in 1895).

61. Aron Rodrigue, French Jews, Turkish Jews: The Alliance Israélite Universelle and the Politics of Jewish Schooling in Turkey, 1860-1925, Indiana Univ. Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis, 1990, p. 53.

62. Esther Benbassa and Aron Rodrigue, eds., A Sephardi Life in Southeastern Europe - The Autobiography and Journal of Gabriel Arie, 1863-1939, Univ. of Washington Press, Seattle, 1998.

63. The Crespin surname appears repeatedly in lists of Jewish brides and grooms of Izmir for the late 19th and early 20th centuries (see Roland Taranto article “Les Noms de Famille Juifs de Smyrne,” supra, pp. 6, 8), and of Jews buried in Izmir after the 1920s. A number of Crespin lived also in the Sephardic community of Salonika, until Nazi Germany destroyed the community. The Germans deported Salonikan Jewry to the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp.