Thanksgiving

By Judy Belsky1

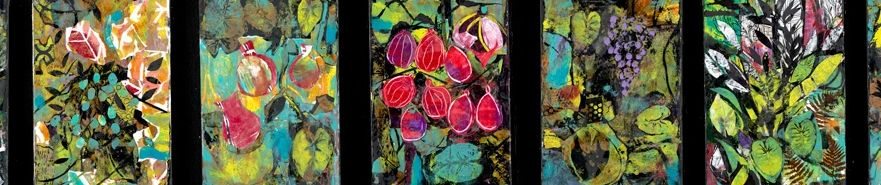

From the seven species, 2018-2020 courtesy of the artist, Judy Belsky

My father loves the United States and especially the Pacific Northwest. He is deeply grateful for the freedom, opportunity and the natural beauty he finds there. He leaves his native city of Manchester, England after the Industrial Revolution stained its bucolic green spaces and surrounding rivers with factory smoke and smog.

We graft Jewish gratitude on to the day of Thanksgiving. When I am eleven, my dad and I leave the house filled with the sweet and savory fragrance of roasting and baking to attend special prayers at the synagogue started by Jews from the Isle of Rhodes. Our synagogue, a mile away, was founded by Jews from mainland Turkey. I know many of the families here. But beside us and a bit further back sits a row of lovely women silently weeping, their complexion darker than most of the Sephardim I know. As the congregation prays for the safety of the government that shelters us, they weep. Memorial prayers are said for lost loved ones. They weep. I imagine that as they weep, their tears turn their faces dark. For I am black but beautiful (Song of Songs).

Deep in gravitational pull to the grieving women, I ask my dad about them. He explains how the Nazis devastated the Jews of Rhodes and Salonika. These women cry for loved ones who were killed. I see their faces suffused with pain, inconsolable.

This evil surrounds us like a heavy mist. My breath is constricted. But somehow in the car on the way home with him, the air clears.

Bringing in the light

Courtesy of the artist, Judy Belsky

Over the years, I hear myself say: our family did not experience the Holocaust. Sephardic Holocaust discussions often turn to Salonika and Isle of Rhodes, leaving Turkey in a kind of pink twilight. My selective focus conceals the truth and its impact. What is the truth? Why did I wait decades to uncover it?

Turkey did not send Jews to the gas chambers. The only neutral country to enact racial laws, they conscripted Jews to forced labor battalions; made tax laws that left them impoverished; forced them to leave their homes and relocate; bowed to Nazi demand that Turkey repatriate their citizens abroad leaving them vulnerable to deportation to concentration camps. Stripped of statehood, many were sent to perish. In 1934 a series of pogroms occurred against the Jews, one in the town of Tikir Dag where my family had lived just ten years before. If my grandparents had remained there, the family might have been injured or killed. The government failed to intercede. As a consequence of violence, 20,000 Jews fled to Istanbul. In 1942, the ship Struma carrying Jews from Romania to Palestine stalled in Turkish waters. Refusing to grant them asylum, the Turks towed the ship north of Istanbul where Soviets torpedoed them. Of 769 aboard, one survived.

For Jews, during the war years, Turkey provided a shelter made of mesh. The holes kept getting bigger.

For six decades my fists clench over two hard rocks of history. Slowly released now, exposed to light, two palms open. I read the twin messages now in their proper order: Because my grandparents left Turkey to avoid their sons being taken to the Turkish army, we were spared when the Jews in Turkey were exposed to racial discrimination, starvation, violence, loss of citizenship if they dared leave. The slippery slope to Nazi Germany was never far away. But for this Grace of G-d’s timing, we sailed safely to Seattle.

What does my refusal to integrate the two truths do for me? Does it keep me safe from trauma? Does it perpetuate a belief that I am Invulnerable? That I am separate from those who perished? Separated by an invisible mechitza from the survivors?

Facing history, I face my fear. I am more alive. I am less avoidant. More afraid. And less afraid. Less self- protective. More vulnerable. More authentic, I stand before G-d, awakened in awareness of danger. With utter need and sheer gratitude my only offerings, I enter the present as never before. When I crack it open, I crack myself open. I chisel stone to reach me. The cold stone falls away and leaves a live, beating heart.

I float back to the Isle of Rhodes synagogue on Thanksgiving Day in 1958. I leave the seat beside my dad. I stand in front of the weepers. I stand there silently until the women understand that I can see them and I want to join them. They make a space for me by moving closer to each other. We cling to each other and weep together.

I revise my old statement: I experience the Holocaust.

Many years pass. We make our home in Israel. In the fall of 2003, two Seattle cousins and their spouses invite us to join them mid-November on a roots trip to Turkey. Hillel cannot take the time but urges me to go. I am in the process of writing some of my family history and I feel excited about a first trip to Turkey. But by the next day, I am inexplicably down on the idea. I cannot say why. My cousins continue with their plans, but in the next week or so, one of the couples finds they cannot make the trip, so the trip is cancelled.

On November 15, terrorists set off car bombs during Shabbat morning services devastating a synagogue in Istanbul, killing worshipers and passers-by. The name of the synagogue is Neve Shalom, the one we would have attended had we made the trip.

1 Judy Belsky is a writer, clinical psychologist, and artist. She lives in Israel. She has published a memoir and several volumes of poetry. One of her main themes is her Sephardic background in Seattle, Washington. A second memoir is in progress entitled The Passover Scarf.